A DESERT RAT'S STORY

Home Page Previous Page Next Page

CHAPTER 2

Boxing

BOXING DAYS

By the time I was eight years of age boxing started

to interest me, so Dad enrolled me at the Caius Boxing club in Battersea,

a club at the time started by students at the college bearing that name in

Cambridge. I was taught by Tosh Hamlyn, a former boxer, and Johnny Peters,

who had fought for the World Light Weight professional boxing championship

and was then at the end of his career. Johnny had a huge cauliflower ear.

Both taught me so well that I entered the boys Westminster Schools Championships

held at Watney’s Brewery at their depot in Victoria Street. From then

on I won at each weight year after year.

We had inter club matches against Devas, Battersea, Downside, Fitzroy Lodge

and other locally famous amateur clubs. The events would be staged at neighbourhood

public halls, admission six pence. If a boy won, he was given a small silver

plated cup - mine are still here in the garage - and all the participants

got a char and a wad (a cup of tea and a thick cake). They were very happy

days for Dad and myself. We both loved the atmosphere of the training nights,

the smell of embrocation applied to aching limbs, the camaraderie of boy boxers

taking it all so seriously. Even from the young age of eight upwards, we all

had the same aim - that one day we would compete and win an Amateur Boxing

Associating title, an annual event.

Dad had been out of regular work for over two years. It was a hard period

at home but then Mum managed to get a job as a cook and started bringing home

some better food. Mum worked so hard and always made sure we children came

first. She was away from home most of the day. On Friday evenings she and

her sister Lily walked over a mile to Lambeth Walk to do the shopping for

the week. Lambeth was then full of stalls selling produce, sometimes a halfpenny,

or even a farthing, cheaper than on Lupus Street. We would watch from our

window for them to return around two hours later knowing that Mum would have

bought us each a small bar of Cadbury’s Milk Chocolate, costing penny

each. She never missed on that one.

A special treat for us was a visit to the Biograph Cinema in Wilton Street

near Victoria Station. We had been given two pence each on a Saturday morning

for the show commencing at 0.00 a.m. Syd was about five years old at the time

and Kitty and I walked with him between us. Arriving early, we were disappointed

to learn that in fact the cinema did not open until .00 p.m. Kitty and I were

of the opinion that we would have to give the money back if we returned home

early, so we decided to wait outside until the doors opened three hours later.

In those days the programme would be for two films with an interval between.

As a consequence, we did not arrive home until almost .00 p.m. and found Mum

and Dad frantic with worry. Syd was blameless and got his fish and chips,

but we were sent off without supper. Syd saved some of his for us, that being

his nature, but it was not necessary as a little later Mum came to us and

gave us our share.

Dad tried many ways to earn a little money. Making needle threaders was one.

This involved cutting out a piece of tin inch square, folding and placing

within it a piece of thin wire formed in a four-sided elongated shape, so

that it protruded from one edge. This would be inserted into the eye of the

needle, and one would thread the cotton through so when withdrawn, one could

pull the thread through with it. These he tried to sell from door to door

for three pence each. Sometimes he got an extra two pence, but it was hard

work for him and eventually he had to give it up as it took too long to sell

just ten of them during a whole day.

WARWICK SENIOR SCHOOL

On reaching the age of ten years we were allowed

to leave Warwick Junior and transfer to Warwick Senior, a gloomy Victorian

building situated next to Ebury Bridge a short distance away from our home.

Kitty being the eldest was the first to arrive there. She was a very spirited

girl, a little cheeky at times, but pretty and intelligent, and she soon settled

in and had many friends. I looked forward to going there.

The Headmaster, Mr. Whitehead, had an extraordinary resemblance to the posturing

Italian dictator Mussolini - bald head, chin thrust forward and a rather severe

visage. Mr. Whitehead imposed a hard discipline but was fair compared to Ayres.

Punishment for boys was three on the backside. On one occasion Fatty Billam

was asked to touch his toes in readiness. One of his arms was permanently

bent due to a breakage some years earlier. Mr. Whitehead told him to straighten

his arm and Billam replied, “ I can’t, sir, it’s been broken.”

He was then told to go back to his classroom unpunished. It showed a humane

side to Mr. Whitehead’s character. I still got mine though.

The teachers were all good. One, named Mr. Pope, had served during the 1914-18

war and clearly could not forget what he endured. He enjoyed teaching and

had a great sense of humour. We all chatted a lot when his head was turned

towards the blackboard but he had an uncanny knack of knowing who the principal

miscreant was. He would whirl around and with great accuracy throw a small

piece of chalk at whoever had been making the most noise. Topsy Harris was

seated next to Snowball Walsh, a ten year old with cropped, almost white hair.

They both lived in Peabody Buildings. Mr. Pope threw a piece of chalk at Snowball

and called out, “What are you laughing at Walsh?” Standing up,

Snowball replied “Please, sir, Topsy Arris farted.” Mr. Pope managed

to control himself as most of the class exploded in laughter but completely

lost his composure when Topsy, brick red in the face, yelled out, “OO

I didn’t.” The whole class screamed with laughter.

Oddly enough I clearly remember Mr. Whitehead asking at assembly one morning

whether anyone present knew that today had a significant date. No one knew.

He then announced that the date was 1/2/34, which would not occur for another

00 years.

At the age of fourteen years we all left school on a Friday to start work,

any kind of job just so long as some money came in. Kitty was the first to

leave on a Friday and commenced work the following Monday at Bolsoms, a furniture

wholesalers just off Lupus Street. The pay was 2 shillings a week (10p). After

one month she was asked to leave as she was cheeky to the foreman. It did

not take her long to get another job with even better prospects. Then she

dropped being a tomboy, started buying pretty clothes and really settled down.

Syd never followed us to this school - he was so much brighter he was offered

a place at Buckingham Gate School, where he could continue his education until

the age of sixteen years, but war broke out and Syd, too, left school at fourteen

years to get work and help out at home.

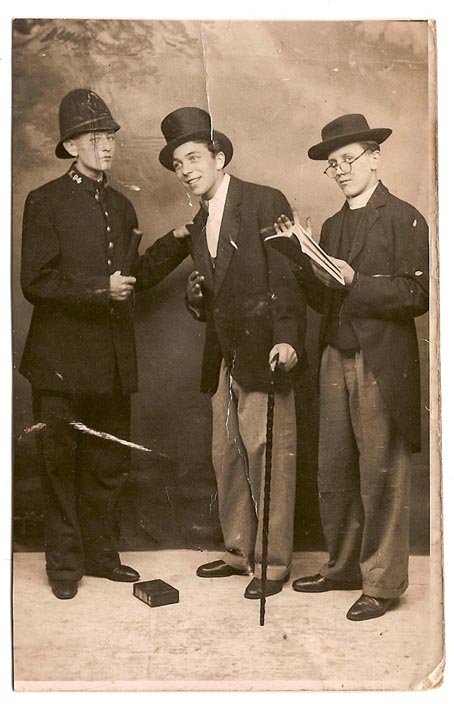

Eddie Wallace, Ted Hartland, Neddy Dowrick - Southend, 1938 (Ted aged 16)

MESSENGER BOY

My first real job was at the News Chronicle newspaper in

Bouverie Street at the age of 4 years. I was paid 4 shillings a week (70p)

and started right at the bottom as a messenger boy in the Advertising Department.

Being rather good at art, I thought, as Dad did, that it was a step up the

ladder leading to the being in the office rather than running errands. There

were about fourteen boys seated around a large table. When a buzzer sounded,

Mr. Copping, who was in charge of all the messengers, would send the next

boy in line to the office concerned. He would then have to take the sample

prints to the various advertising agencies. I was so proud of my first pay

packet I wanted it left unopened until I got home to Mum, so I was going

to avoid the bus and walk home.

As I came down the steps from work, Dad was waiting for me and we walked

to the bus stop in Fleet Street. The conductor came around and Dad asked

me to pay. I opened the packet and complained throughout the journey. On

arriving at No. 77, Dad said to Mum, “For goodness sake give him two

pence.” I realised then that my poor father did not have the fare,

not even two pence -he was having a tough time. I gave my mother all the

money and she in turn kept just 2 shillings. My pocket money was the remaining

one shilling and eight pence, four pence having been deducted for insurance.

This was normal at the time as all children were expected to help their

parents upon having started work.

I enrolled at the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts and went twice a

week to evening classes. The News Chronicle encouraged this and those studying

were allowed to use the adults’ canteen for a light snack, costing

up to six pence, before leaving the building. The first three months I practiced

lettering of all types, then later simple designs for aircraft advertisements.

I really enjoyed it and kept up my attendance for over a year.

Having been at the News Chronicle almost a year, I had a talk with Mr. Copping

about the prospects of employment in the advertising office or studio, I

was told that all messengers were dismissed at age 16 years and that it

was impossible for any of them to make progress. He explained the significance

of the trade union movement and told me that all employees were members,

and their sons automatically got any vacancies in the newspaper industry.

On hearing that, I gave notice to leave the following week. Mr. Copping

was quite right - until a few years ago newspaper proprietors were forced

to employ three times the employees required to operate the machines and

a strike would be called for at every opportunity, the members always ganging

up against efficiency and the so-called “bosses” who paid them

well.

I got a job a few minutes away from our house at a firm of printers specializing

in making coloured posters for cinemas which advertised the following week’s

shows. The posters were in two colours, red and blue, and the lettering

was cut out from waterproof paper and then pinned to gauze. My job was to

roll the first colour on, wait for it to dry and then apply the next coat.

It wasn’t all that artistic but it may have led somewhere towards

my ambition of being in the art world, even if at a low level. From day

one I arrived home smothered in paint which was difficult to wash off. Mum

became very worried as to the permanent effects and said I should leave

the job. So the following Friday at 4 p.m. I gave notice and left. I was

fifteen years old and getting nowhere. I looked on the past year as a complete

waste of time.

Wandering the street the following week, I saw Mr. Whitehead approaching.

As he drew level he enquired why I was not at work. On hearing that I was

then unemployed, he said that a firm of pipe makers to whom he had recommended

one of his former pupils had asked him to supply another. Giving me the

address, he suggested that I report there the next day. When Dad arrived

home I told him that I was to be trained as a plumber. He was delighted

to get this news - a skilled craftsman would always have regular work.

The address given was Alfred Dunhill & Sons of Duke Street, St. James,

high quality cigar and tobacconists who also sold some silver and gold items.

The Royal Warrant was displayed as well as those from other Royal families.

The premises were luxurious and when I entered and saw the display before

me I knew that plumbing was definitely out. I was interviewed by Mr. Phipps,

who wore a black morning suit, striped gray trousers, a white shirt and

highly polished black shoes. He spoke with a London accent similar to mine.

He asked several questions and then told me to write my name on a piece

of paper. As I was doing so he asked whether I always bit my finger nails.

Quickly I replied, “No but I always keep them well cut.” With

a smile he replied, “Well stop cutting them and you can start here

next week.” The pay was 15 shillings a week (75p), paid every two

weeks.

On the first morning I was taken to a desk at the corner of the shop where

all clients entering could leave their cigarette lighters for re-fuelling

and cleaning. This service was free and, to my surprise, most of the clients

would tip half a crown to whoever did the job. Occasionally the junior salesman

would volunteer to give us a break while they made enough for their lunch.

Salesmen all wore long silk frock coats, grey in colour. Boys had to make

do with an ordinary cotton coat. All of them were very well spoken and several

spoke another language. Mr. Phipps said that if I learnt French he would

give me a raise in pay. A month later I found a lady to teach me, Madame

Robert living in Sutherland Street, a widow who said she would teach me

eight lessons for £1 paid in advance. I stayed with her for over a

year.

Members of the Royal family came to the shop and Prince Bernhard of the

Netherlands was a client. When Cary Grant came in, I was told that at one

time he was married to the richest woman in the world, Doris Duke. He was

always deeply tanned, had a very small pointed nose and was very polite

and modest, perfectly at ease with everyone. I was most impressed to be

here - it seemed a glamorous establishment to be working in, even as a boy

filling lighters earning less than one pound a week.

The boy who preceded me was named Watts, who was now speaking with a ghastly

fake posh accent I could barely understand at times. One very hot day he

said that when he got home he would like to lie in his bath for a long time.

Not wanting to be outdone by admitting we didn’t have a bath at our

flat, I replied that it also was my intention - quite a rash thing to say

as it transpired. I walked to the public baths, paid my two pence and was

given the small piece of hard soap and the usual rough towel. I went upstairs

to take my place on the bench to await my turn. Watts was already seated.

He blushed and quickly said that his bath had broken down. Neither of us

swanked after that day.

We had been using the baths for years. The taps were outside the bathrooms

- all single. A little gnome of a man armed with a huge brass key would

turn the taps on. The water would gush out at a very powerful rate. Once

in the bath we would shout out, “More hot water No. 55” or cold

if need be, and after a while the little man would come scurrying along

to attend. It was a great trick to call out your friend’s number and

hear him yelling as the cold water poured in. If he heard us before the

man doused him we could hear him shouting, “Don’t, don’t!”

I kept up my boxing and had won the South West Divisional Championship of

Great Britain. Having beaten most of the area champions, I was entered for

the London Federation of Boys Clubs Championship and fought twice in the

same evening, winning the event at my weight, knocking out both my opponents

and getting a black eye in doing so. Dad tried getting the bruising out

on the Sunday to no effect and I arrived at Duke Street the next day with

a real shiner. Mr. Phipps was doing his usual stroll around the shop floor

and paused before me and asked how I got my eye blackened. I replied that

it was done by an accident at home, On hearing this he said that he had

been at the Holborn Stadium seated two rows from the ringside and had seen

a lad looking very much like me bearing the same name. He later told me

he was a former boxer himself. He said he thought the scraps were great

and that a 10 shilling raise would be in my next pay packet.

With the extra money coming in I could afford to have lunch in the cafes

in the Duke Street area. On one occasion I decided on a quick visit home,

which would just allow me twenty minutes to get a snack. To my surprise

Mum was in the kitchen quietly ironing some clothing, saying very little.

I was dashing around and was possibly abrupt as I spoke to her. As I left

I turned at the door and saw that she was quietly weeping. I was very upset

at this and worried the whole afternoon that perhaps it was my attitude

that caused her to be so upset. Arriving home that evening I was told that

Mum was pregnant and was very tired. It had been thirteen years since Syd

had been born.

When Mum became pregnant with Viv in 9 8 it became imperative that we move

to a larger place, and Mum’s sister Lily found us a flat near to her

own in Offley Road, Kennington, not far from the Oval Cricket Ground. Mr.

Hardiman expected to come with us and on being told that this was not possible,

he withdrew and never spoke to any of us again. Reflecting on the matter

now I can understand his disappointment as he was elderly and alone and

did not want any change in his comfortable situation.

Before we departed Westmoreland Street, the two rooms and the landing were

scrubbed several times until spotlessly clean, including the Linoleum-covered

floors. Mum was always a stickler for cleanliness, not only with the rooms

but with ourselves. We had to change our underclothing regularly. We each

had two sets. I remember one of her oft repeated sayings, “Change

those dirty underpants, Teddy, you may get knocked down by a bus and what

would they think at the hospital.”

The flat above our new place on Offley Road was occupied by a widow with

two very attractive red headed daughters age 16 and 17, both of whom I took

out to the pictures on different occasions. I only did that once as I could

clearly hear them chatting about it - their bedroom was just above mine

- and they were having a bit of a laugh over what was supposed to be confidential

conversations I had with each of them.

On the floor above them lived the Abelsons, a Jewish married couple with

a young son. The father earned a living “on the knocker” - buying

scrap gold. He was very flashy and a bit of a wide boy, and the wife was

a very flirty buxom peroxide blond, quite an unusual family, The top floor

was the home of two very elderly strictly Orthodox Jewish brothers, desperately

poor, never without a head covering, ancient long black overcoats reached

their ankles. They must have been in their seventies. Catholics, Protestants

and Jews all lived together in harmony. None of us considered it in any

way unusual. All in the building were always very hard up but contented

with our way of life.

I left Dunhill’s soon afterwards as the journey to and fro was too

complicated. I got a job locally, in Coldharbour Lane, Brixton, at the Sample

Shoe Shop selling lady’s shoes. The owner of the shop would travel

to Northampton every month and buy all the rejects. Some were ghastly but

cheap. All the stock was priced in cost code. We were paid a share of the

profit on top of a low wage. A pair costing 10 shillings would stand a double

up. If sold, we would yell out to Mr. Woodcock , “Free make”

and he would scuttle over to sign the chit for an extra payment to us. He

was a tiny man always worried about losing his awful manager’s job.

I never found out why we called out “free make.” There were

six on the staff, boys and girls. We all got on well and had a great time,

making the most of what was a bit of a dead end job.

I was still boxing and unbeaten until I met another unbeaten fighter named

Robert Parker at the Holborn Stadium in finals. I had beaten the Champion

of Wales and never considered losing to anyone at my weight. Tosh Hamlyn

was in my corner that night. We were both very confident, having never been

beaten and finishing all my fights by a knockout . I took my -year old girl

friend with me hoping to impress her. In the first round I gave him a boxing

lesson. The bell rang for the second and, over confident, I arose from my

stool far too slowly. Parker had run across in a flash and quickly put a

right hander on my chin. Down I went. Up again at eight, I clearly heard

my girl scream as I took another, then it was over. It was my fault - how

many times had Tosh said, “Get your hands up to your chin as you arise

from the stool and watch your opponent at the same time.” Later all

the boxers got a ticket to Lyons Corner House for a tea and a cake costing

sixpence.

A year later both Parker and I were in the forces. Parker eventually joined

the Physical Training section of the army and remained in England throughout

the war years, becoming Imperial Services Champion. I left home and was

abroad on and off for the next six years. Parker turned professional on

his discharge and after a few fights was badly damaged in an eye. He had

to retire early. At one time I heard that he fought Randolph Turpin, our

World Middleweight Champion who eventually lost to Sugar Ray Robinson. A

short while after that loss, being broke and dispirited, Turpin committed

suicide - one of the best fighters we ever had.

The new baby arrived on 11 February 1939, a pretty girl who was named Vivienne.

Dad was very proud to be a father again.