A DESERT RAT'S STORY

Home Page Previous Page Next Page

CHAPTER 3

War Breaks Out

THE ONSET OF WAR

For some while now we had been getting news of events taking

place in Germany, led by a peculiar man with a Charlie Chaplin moustache named

Adolf Hitler who had built up an enormous army, navy and air force. Hitler’s

declared ambition was to conquer Europe and expand the living space of Germany.

A posturing dictator with a charismatic speaking manner, Hitler first laid

claims to Austria. Then, by marching into Poland, with whom we had a defence

agreement, he brought England to the awful position of backing down to avoid

a war or keeping our obligations. An ultimatum was given to Hitler by Prime

Minister Neville Chamberlain to withdraw from Poland or risk the consequences.

No reply came, and our country declared war on the rd September 9 9.

It was a sunny morning when the news was announced that we were at war with

Germany. Many thought that we would be bombed at once and got very upset.

Nothing happened though, and we entered what was to become known as the “phony

war.” I was surprised by my own feelings of exhilaration, probably fed

by my thoughts of release from a job which, when compared to the adventurous

life of a soldier, did not bear comparison. The thought of me being injured

or mutilated or even killed just never entered my head; that sort of thing

happened to other people, and wounds were always in the shoulder and soft,

not dangerous, parts of the body.

Meeting up with some of my friends, I was very surprised to learn that none

of them had any desire at all to volunteer for the services. I momentarily

questioned myself if it would really be wise to give up a job with the unlikely

prospect of being able to find another when the war would be over in a matter

of three months. The newspapers had declared that Germany would run out of

oil and petrol within this time, and the whole world knew that the British

Army and Navy were the finest of all and, once mobilised, would crush our

enemy before Christmas. I just could not wait to get in!

Within a short while our family split up, myself in the Army, Kitty in the

W.A.A.F. and not all that long after Syd to the Navy, Dad to the Air Raid

Wardens, and Mum as a cook at a Training College. It was six and a half years

later before we all met, but we never lived together as a family again.

The nearest Recruiting Office was situated in Whitehall. I walked there early

on Monday morning, the war had only been declared the previous day and I was

anxious to get in before it ended. Standing at the entrance was a huge Sergeant

of the Life Guards who, as I approached, enquired what I wanted. On hearing

that I had come to join up, he told me in very fruity language to “F…

off.” I rapidly came down to earth then, and as I walked away, I decided

to wait until my age group was called up. So I settled down, continued with

my job and envied everyone in uniform. I was seventeen years old and reconciled

to await my call up, although I thought I’d probably never get in as

the twenty year olds were getting their papers at that time.

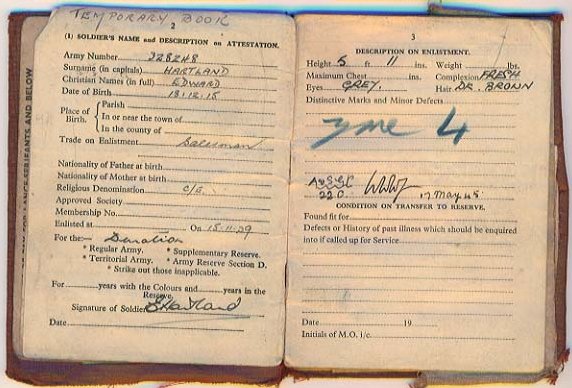

Ted Hartland's army book, giving a false date of birth

A few weeks later, sitting in the basement watching Mum ironing, she said

“I suppose you will be joining up soon, won’t you Teddy?”

I looked up startled and saw that she had not raised her head as she spoke

the words, probably just thinking aloud. The matter was farthest from my thoughts

at that moment, but her question kindled my excitement and I decided to try

again. I altered the date on my birth certificate but made a complete mess

of it - I gave my date of birth as 8th December 1915, adding six years to

my age -and headed for the Recruitment Office in Croydon. Eight hours later

I arrived at the house and announced that I would be leaving home in two days’

time. I was given Army No. 328248 as listed in my AB 64 (a record of service,

illness, rank, etc.). I had asked to join a cavalry regiment purely because

the uniform seemed more glamorous than the ordinary infantry. Cavalry wore

breeches, spurs, bandoleers, swords, sword belts and highly polished boots.

The pay was two shillings a day and I made an arrangement to make Mum an allowance

of six pence a day whilst I was away from home. Many years later Syd told

me that after I left they were so hard up, this small amount of three shillings

and six pence came in very handy at the end of the week. Syd left school before

his fourteenth birthday, got a job and handed over all his pay minus a few

shillings, most of which he gave back to Mum the following Thursday. Syd always

looked after Mum by giving her whatever money he could save. He was always

a very kind hearted person.

The day before I departed, the Air Raids Warning sounded late in the evening.

We had no way of knowing whether we were in danger, so all the inhabitants

of the house came down for shelter in our basement flat and huddled together.

The last to arrive were the two orthodox Jewish brothers from the top floor,

petrified with fear. The red headed girls could stand it no longer than five

minutes and went upstairs to take their chances. After a half an hour the

all clear sounded and all returned to their rooms above.

A rail pass had been issued to me and I headed for the th Cavalry Training

Regiment, stationed in Shorncliffe, Kent. On arrival I was allocated a space

in a barrack room with twenty-four beds. The next day the Sergeant Major marched

all of us to the barber shop for a very short haircut. The barber took great

delight in practically shaving my head bare, as at that time my hair was fairly

long. To add insult to injury, I had to pay. I have always thought that the

Sergeant Major and the barber were cohorts and divided the spoils at the end

of the day. They just wanted a long succession of rookies to come in the camp

and help them on to a large fortune. Both were long service regular soldiers

and unlikely to be in any danger of experiencing full active service as they

were headed for a pontoon (2 years service) with a pension at the end.

We were paraded for inspection every morning by a stiff looking Captain who

strolled along in full uniform with highly polished brown riding boots. He

looked at least sixty years old with white hair and moustache and quite clearly

wore a corset. He held himself upright with some difficulty, and he looked

at us with barely concealed contempt. I wondered at the time why, with all

those years of service including the First World War, he had only risen two

places in rank.

A group of Sergeants who had been on reserve and called up on the outbreak

of war were in charge of drilling us and teaching the basics of army life.

We had all the usual insults about our lack of knowledge and I must say that

at the beginning this was true. One particular Sergeant really put himself

out to be as unpleasant as possible with our squad but he made the mistake

of insulting a fellow named Trooper Smith, a real tough South Londoner. One

morning the Sergeant arrived on parade with a terribly battered face, and

from then onwards he got the message that all of us were volunteers from all

walks of life - solicitors, accountants, navvies, villains - all convinced

that we were in the army for just a few months.

We attended riding school, contained in a large building with

a floor covered with a deep layer of peat and several fences to jump over.

Falls were many, but we learnt how to ride as well as muck out the stables.

When outside, we practiced charging with a sword at a bag suspended from the

bough of a tree - this was supposed to be the enemy – and were taught

to throw ourselves from the horse onto the ground and aim at oncoming tanks

with a Boyes rifle which fired a bullet half an inch thick. This would hardly

penetrate a piece of wood let alone the sides of a tank. We realised then

that we were very short of proper armaments and that all the talk of Germany

being weak was untrue. In fact, at the time Germany had the most powerful

army in the world, with huge tanks, and had been rearming for many years.

As I mentioned, our cavalrymen uniform consisted of a tight jacket with brass

buttons, riding breeches, sword belt and sword, leather bandoleer, heavy boots,

spurs and a peaked cap, and also a gas mask. I was very proud of my uniform

and wore it when I went into the nearby village of Folkestone, to a dance

at the Leas Cliffe Pavilion. I was asked to remove the spurs. I was seventeen

years old. liked the uniform and never thought for one second that I would

ever be in danger, only that this was an exciting interlude and a welcome

break from boring Civvie street.

Having learnt how to ride and take care of our horses, in time we became very

much attached to our charges. We had guard duty to perform every few days

consisting of two hours on with four hours off. During this time we patrolled

throughout the night and saw that the horse blankets were to be kept on, but

every time the blankets were straightened out the horse would shake it off.

At this moment invariably the duty officer would stroll by and see the mess.

Punishment was confinement to barracks a few days, a bit unfair but we quickly

learnt not to complain; those that did got a double helping next time. Food

was plain and quite good. Many of the lads came from very poor families and

had never eaten so well. We sat at tables for twelve in the mess hall, and

every day the Duty Officer followed by the Sergeant Major came to enquire

whether we had any complaints. On the whole there was not a lot to whinge

about.

On the 8th December 1939 I was told to report to the Orderly Office, and then

was marched in by the Sergeant Major and made to stand to attention before

the Commanding Officer. The CO stated that my father had written to say that

I had joined under age and that he was applying for my discharge from the

services. The CO carried on to say that boy bandsmen were serving at a younger

age than I and therefore I should stay in. He then commanded, “March

him out, Sergeant Major” and it was “Left right, left right”

and I was out of the door in a flash.

Over fifty years later, when going through some of my father’s papers,

I found his first discharge papers dated 7/11/1915 -reason for discharge “giving

a false age on enlistment.” By then he had served 225 days and his height

was given as 5' 3" and his age 19 years. He joined up again a few months

later, was sent to France in the East Surrey Regiment, was gassed and then

taken prisoner, and he remained in the camps until the end of the war.

The first person I happened to chum up with was Les James, a very cheerful

fellow from London. He was six years older than me and was very street wise.

From day one he was determined to keep out of trouble and away from any danger.

He was fairly short, had a ready smile and was always on the make. It was

announced that we could all go home for a weekend leave on condition we did

not use the railways but made our own way. Les rushed into Folkestone and

hired every coach in town, then offered seats at ten shillings return. I asked

whether I would have to pay as I was only drawing that amount as a weeks pay,

and he replied that without that little bit he would make a loss so I had

to pay the full whack. He was always pretty careful with his money and it

surfaced many times during the next six years. He is still around, now over

90 years old, living in Denmark running a Dolls Museum in Ebeltoft. When he

reached the age of 70, I remember him saying that he and his wife were going

to start spending money, but she died a year later and he, without children,

now lives alone. I wonder if he ever changed from being penurious.

We got used to riding around on horseback and rode all over the area. Folkestone

was quite a good place to be. Two or three times a week we would visit until

the money ran out. Every Sunday we had Church Parade, which involved a march

to the church, a long sermon, and an even longer hymn while the plate was

passed around. Our boots had to be polished very bright. This was done by

boning out all the small dents on the surface and then rubbing in polish and

spitting on it and polishing in again until it was mirror bright. I suppose

this was where the expression “spit and polish” came from.

Out riding one day I was thrown from my horse which ran away. I trudged back

to camp several miles away. I did not know what to do. Seeing the NAAFI (clubs

and cafes established by England’s Navy, Army and Air Force Institute),

I headed in for a char and wad. Sitting there with my pals, the door flew

open and in stormed a Sergeant demanding to know who was the Squaddie who

left his horse to go charging into the local market causing a great disturbance

among the stallholders. He put me on a fizzer (a charge) and I made another

visit to the Commanding Officer expecting at least fourteen days Jankers,

but the Sergeant made it sound funny with his description of me, feet up in

the NAAFI eating a rock cake while my horse charged around among the tomatoes.

I was let off without punishment. I should think it made a good story in the

officers’ mess that night.

Ted Hartland in uniform, 1939

After three months we were given a seven-day leave pass subject to recall

to camp if an emergency arose. I arrived in Offley Road, Brixton to find that

the two redheaded sisters had departed together with their mother. Their flat

had been taken over by Mrs. Rowe and her eighteen year old daughter, Rosie.

Mrs. Rowe spoke pure cockney and prefaced every remark with the words “ere

then.” She was very dowdy in dress and looks, though Rosie was an astonishingly

beautiful brunette, was well dressed and spoke quite decently. None could

reconcile ourselves to the knowledge that they were mother and daughter. Mr.

Rowe was never mentioned. Rosie and I became great friends.

Mr. Abelson was still “on the knocker” and carefully avoiding

his call up. The devout Jewish brothers still got panic stricken at any sound

of an airplane. They had so little money I felt sorry for them. They were

decent people but no one could help, no one had any money to spare. I do not

know whether they survived the war years. What was amazing was the contrasting

appearances and occupations of the twenty plus people living in that particular

house and how we all got along so well. It is still pleasant to recollect

how on warm evenings we would sit on the steps outside chatting away. The

week went far too quickly and I said goodbye to Mum and Dad and little Viv

and to Rosie and all the others, not thinking that apart from Dad and Rosie

I was not to see any of them again for over four years.

On arriving back at Shornecliffe Camp we were given the news

that our th Cavalry Training Regiment would be moving to Colchester. This

we found to be a huge and very unpleasant place. The commander of the entire

camp was named Colonel Radcliffe, a friendless man who walked or stalked through

the camp with what he thought was a fierce warlike expression on his face.

As he was quite elderly, he was unlikely to be involved in any dangerous activity

and his time was mainly occupied in peculiar disciplinary activities. This

involved paint, in particular Red Raddle, which was dark and very matte once

applied. Every part of the camp which could be painted got a dose of Red Raddle.

He got enraged if he found a bare spot. Quite naturally he became know by

the name of Red Raddle Ratciffe. No doubt throughout the war years he had

quite an easy life and enjoyed the adulation of civilians with his uniform

and high rank, but he caused untold inconvenience to thousands of cavalrymen

with his obsession.

The stables at Colchester were huge and each held about thirty horses in six

blocks. We had guard duty during the night, two hours on with four hours off.

A duty officer inspected during the night. Just like at Shorncliffe, our job

was to keep the horse blankets on the horses’ backs, very difficult

to do as the blighters shook them off as soon as our backs were turned. As

a consequence, by the time one got back from Stable Six to Stable One all

the blankets were off just at the precise moment that the Duty Officer walked

in. Protests that the job had been done properly fell on deaf ears, and the

usual punishment was seven days confined to barracks.

After two months we all moved to a farm six miles away. We exercised our horses

throughout the day and slept on the floor of the stables. Riding around the

countryside on a summer evening was ideal, and I wished that it could have

gone on forever. The war seemed very far away but then came the terrible news

of capitulation of the French and our army’s desperate and difficult

escape from Dunkirk.

Life at our farm did not change for some while. During the evenings there

was little to do except play cards. I had so little money I avoided it. However

one night I joined in just to make up the number. Beginner’s luck, I

won three pounds, a small fortune to me. I wrote to Dad asking him to come

and see me. Knowing he was very hard up, I offered to pay his fare and told

him that I would meet him at Colchester Railway Station on the following Sunday

morning.

Two days later I played again and lost every single penny within five minutes

flat. There was no telephone at home and I had no way of stopping Dad from

coming the following day. I stood on the platform waiting for him, dreading

that I could not give him his fare money. As the train stopped, the first

to step off was Rosie dressed in a very expensive looking lilac coloured dress!

After a quick Hello I asked her to go to the waiting room as I had seen Dad

step down from the far end of the train. As he started to walk towards me,

I rushed up to him and asked him to lend me ten shillings, explaining that

Rosie had unexpectedly arrived and that I wanted to take her around town.

Looking shocked, he said, “I thought you would be giving me some”

and I had to tell him that I had lost the lot the previous night.

Sadly he took the money from his pocket and handed it to me. I said that I

would pay him the next time I came home. I am ashamed to say that we said

goodbye and I left him alone to take the next train back to London. I have

had seventy years to think of this incident and still I do not know it didn’t

occur to me to spend the day with both of them. After all, they lived in the

same house and were friendly. Rosie and I were eighteen years old and just

good friends. I never saw her again after that day and as for Dad, I did not

see him again for four years. During all that time I kept re-living that incident

at Colchester Station. Looking back now I realise that it was a very cruel

and selfish thing to do.

The following morning we were told that our training was completed and we

would be going overseas with the exception of Trooper Hartland, no doubt due

to my age. Amongst us recruits was an old sweat acting at the time as an officer’s

batman. He regaled us with his tales of pre-war service overseas, including

the sights to see and all the adventures he took part in. I made up my mind

to somehow or other get on the draft. After a while the batman asked, “Why

not request an interview with my officer and volunteer?” I made the

request to go overseas as a replacement for the batman, and he promised to

arrange it and did a day or so later. Probably the batman had been told that

if he could find someone to take his place all would be well. He had been

crafty and I had been the mug by breaking the Squaddies golden rule - never

volunteer.

For security reasons our instructions were to inform no one about our leaving.

Dad had no telephone at home so I had no way of even a little chat. In any

case the matter was not all that serious as I still thought the war would

soon be over and I did not want to lose my only chance to see a foreign country.

So far my only trips away from home had been to Ramsgate, Brighton, and the

occasional annual fortnight trip to go hop-picking in the hop fields of Kent

in the company of hundreds of other South Londoners. I was very excited at

the prospect ahead.