A DESERT RAT'S STORY

CHAPTER 1

The Early Years

PIMLICO

Westmoreland Street in Pimlico, London, is a long row of terrace

houses beginning at a point quite near to the River Thames and Chelsea Bridge

and at the far end the railway crossing of Ebury Bridge. In the early 1930’s

the street was renamed and henceforth became Westmoreland Terrace. Victoria

Station was within a mile, in Victoria Street, with the Houses of Parliament

at its far end and near to the embankment just a few hundred yards further

on. Terrace houses generally had a basement, the ground floor and then two

floors above.

It was here at No. 77 Westmoreland Street that I was born on the 18th December

1921. My father in later years told me that the birth was difficult as I weighed

over ten pounds and Mum was left with two black eyes as a result of the strain.

He never tired of telling me that he had been delegated to cook a meal, and

as a result of all the excitement he forgot it was in the oven and the whole

lot got burnt to a cinder. My sister Kitty had been born on September 10th

the previous year.

Each house had a basement flat with a back yard with high walls The basement

rooms were occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Satchwell and their four children. Mrs.

Satchwell was a rather thin lady, always smiling and very happy with her lot;

the husband a well built good looking man who worked very long hours, taking

only the Sunday off, which seemed to be the norm at the time. Mrs. Satchwell

was a very kind person, always working cleaning her rooms and just waiting

for her husband to come home. Her routine never varied summer and winter.

During the 1930‘s unemployment was very high. Employees could be fired

at an hour’s notice, pay was appalling (average would be around £2.50

per week), and unemployment money was almost non existent. As a consequence,

those fortunate people who had jobs held onto them at all costs and some foremen

of various groups acted like tyrants to those who depended on their whim.

The ground floor had two rooms and a separate toilet at the end of the passageway

next door to the kitchen. The toilet on the ground floor was next to Mrs.

O'Mara’s kitchen. It had a wooden seat and a cistern above with a long

chain, and hanging from the side of the wall would be old newspapers cut up

in squares, threaded through with string and suspended from a nail on the

wall. We were all so near to each other it was possible to judge when anyone

vacated the toilet as we could hear the flush. The man on the floor below

us would occupy it for ages, sitting there smoking his pipe filled with Tom

Long tobacco. The smell would hang around for a long time. We would joke that

he read the scraps of paper whilst he was in there. Mrs. O’Mara, a widow

whose children had long since moved away, always wore a clean white small

pinafore over a black dress reaching her ankles. I don’t think the dress

was ever changed, either that or she had several identical. During the late

afternoons summer and winter she would sit by the window reading her newspaper

by the light of the gas street lamp situated immediately outside our house.

She never lit her own lamp and said it saved her money. Her bed was in the

same room.

She would stand at the street door on any warm day observing what went on

around the street. On one occasion I saw a man approach her and then disappear

down the passageway to use our toilet. On his return a few minutes later I

saw him hand her something. Quick as a flash I was beside her and saw that

he had given her a penny. He must have been a stranger to the district as

at the top of Turpentine Lane there was a public toilet which he could have

used for nothing.

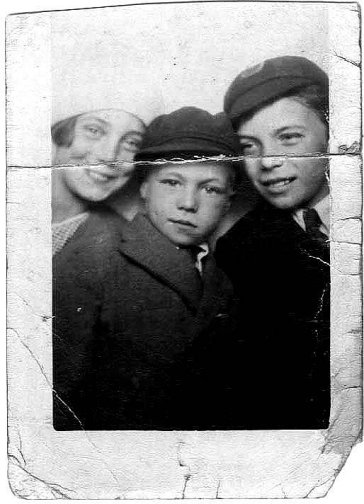

Ted Hartland, aged 6

The first floor also had two rooms identical in size to ours on the floor

above. Our floor on the top had as an extra a small landing measuring 4’

x 5’, a gas stove with wooden shelves above, and in the corner a slop

bucket to take all the liquid waste. One cold water tap was shared among all

those in the house except those living in the basement who had their own tap.

The tap was situated on the outer wall on the first floor and was approached

by opening a glass door on the landing. Regularly the tap froze up in the

winter months. This area was known as the ‘lids’ and was simply

an area surrounded by a small wall eighteen inches in height. The tap was

quite close to the outer rim and we were always warned to take care, particularly

on dark nights. I would peep over this ridge and look down to the yard below.

It seemed to a four year old an enormous distance to the cobbles and very

dark and gloomy.

All the rooms were lit by gas lamps. When wanting to increase or decrease

the light, this could be achieved by regulating the flow of the gas by turning

a small lever at the side. The delicate silk-like gauze lamps broke very easily

and required constant changing. Immediately outside our house was a large

gas lamp post. This was lit and unlit by a man carrying a long pole, who would

use this to turn a lever on and off when required.

On the pavement were four circular metal discs each approximately a foot across.

Coalmen would remove these to tip down the coal to small cellars below. We

all would take our buckets down to replenish when required. A bucketful in

the winter months would last the whole day.

To the rear of Westmoreland Street was a cobbled alleyway named Turpentine

Lane, and on the other side was Peabody Buildings, an enormous block of flats

built, I later learnt, by a Mr. Peabody who formed a trust to help the lower

paid to get a decent place in which to live.

We envied the occupants of Peabody Buildings, as they had a communal bathhouse

where they could have a weekly bath. We were not so fortunate as we had ours

in a small zinc tub which was taken from where it was hanging on a nail on

the lids wall, brought upstairs to our front room and then filled with saucepans

and kettles of hot water boiled on the gas stove. It took a very long time

and baths were taken once a week, mostly on a Saturday night. Kitty would

be first in followed by me and later on by Syd, the water being topped up

with fresh kettles of boiling water. It took two persons to carry the tub

down to the lower floor, then onto the lids where it would be emptied down

the drain and then re-hung on its nail. The whole of Peabody Buildings knew

when we had our bath.

The flats were rented at 7/6d per week, equivalent to 37p. This was collected

by the rent man who called every Saturday morning, knowing that the occupants

would have had a wage come in on the Friday before. During the mass unemployment

at the time, even this small sum was difficult for many families to find,

and on occasion the local pawnbroker came to the rescue. Quite often it would

be a suit or clock to raise the money needed. Pawnbrokers were numerous in

those days, particularly in poor areas.

The key to the house was on the end of a piece of string hanging through the

letter box. I cannot recall seeing any spare throughout our stay. The Yale

type key was not fitted; our key was rather large and difficult to carry around

all day. No house was ever robbed there, being so little inside of any value.

Families were large, anywhere from four to eight children living in a very

small number of rooms. The Hodges lived a few doors away from us. The father

was a road sweeper. All of his eight children were good looking and smart

and cheerful, and on leaving school at age fourteen they all got good jobs.

One of the boys became an apprentice hairdresser. After a month’s training

he would pop into our flat every second Friday night and give Dad, Syd and

myself a quick trim for two pence each.

Nellie Hodge was the same age as myself. We used to go around together. We

both went to the same school up the end of our road, and we both left school

at the same time when we reached our fourteenth birthday. She was very beautiful

and popular and had no difficulty in getting a job with a hairdresser. Years

later, having been given a four-day break after going over on the invasion

of France on th June 1944, I met Nellie Hodge in the Windsor Bar at Victoria.

She was now a glamorous brunette with a wonderful personality. We spent some

time together during which she told me that she had married an American. At

least that’s what she said in answer to my question as to what she had

been up to while I was away. “I married an American” as though

that was a full answer. At least it foreclosed any further interest on my

part. She didn’t seem too happy about having to leave all her family

in England. We never met again, nor did I see anyone from that wonderful friendly

family. I wondered how many survived the war.

Two Irishmen came to lodge with Mrs. O’Mara. Both married and unemployed

in Ireland, they managed to get jobs here, one as a labourer and the other

as a van boy. A van boy’s job was to ride in the back of the lorry and

unload for delivery, swinging to ground level from a rope suspended from the

roof of the lorry. Most of their wages were sent back home. They loved watching

football and would take me with them to see Chelsea play at Stamford Bridge.

Entrance for children was two pence, the same price for a bar of Cadbury milk

chocolate. I would be passed down to the front over the heads of the adults.

The games attracted over 40,000 every home game, and there was never any aggravation

or yobbish behaviour. The two men were very generous with what little they

had, and their kindness I have never forgotten. Sadly they both had to return

to their homeland after losing their jobs.

It was around this time unemployment was very high, not only in England but

throughout Europe. Dad, who was working as a sign maker, became unemployed

and became desperate for work. Despite being gassed during the war of 1914-18,

nothing was available for months. No money came from the State in the form

of unemployment aid. Millions of men who fought in the muddy trenches in the

Great War now struggled to find enough money to feed their children.

One of Mum’s sisters was married to a man in charge of the road sweepers

for Westminster Council, and he managed to get Dad a job sweeping the road.

Pushing a large barrow and wielding a wide stiff brush, wearing a uniform

of a denim type material and a brimmed hat rather like that worn by the Australians,

I would see him now and again and he would call out cheerfully, “ Hello

son.” He did everything he could to feed his family without shame. Looking

back now I can see that it took enormous guts for him to tackle a job like

that, and he was happy to do it and never lost hope for better times. Road

sweeping paid very little money, but it was honourable.

It was a few years later that Mrs. O’Mara died, probably

due to nothing less than old age as she never appeared to be ill from anything

serious. Her small flat was taken over by a man and his wife and two sons.

The father was an interesting character. From somewhere he had obtained a

brown homburg hat and a brown suit. He had a large Bruce Bairnfather moustache

sprouting from his upper lip, giving him a rather solid and reliable appearance.

Every morning he would leave the house and head for Buckingham Palace, saying

he had to be there sharp on 9am. We were most impressed with having near neighbours

with connections to Royal family.

Sadly it was not true. He would stand around the gates and tout for business

as a guide. He had all the patter and his appearance went in his favour. He

got some trade but was constantly moved on by the police as many sightseers

made complaints about the constant harassment from the scores of others, mainly

unemployed, who were trying to earn some money in the same way.

Their eldest son, a soldier, came home on leave prior to embarking for India

where his regiment was due to stay for six years. He regaled me with his exploits

in the services and, as a fifteen-year old, it seemed to me to be a particularly

exciting life. Away he went and a month later a young girl arrived downstairs

heavily pregnant. I recall that her whole appearance was spoilt by her teeth,

which were badly decayed. I wondered at the time whether her boy friend considered

it important as he himself had quite good teeth and was reasonably smart and

good looking.

A taxi arrived outside our house several months later. This was June, 1937,

and such an event was a rarity in Westmoreland Street at that time. We all

stopped to look at who stepped down. It was the soldier complete with kitbag

and pith helmet and various other packages. He claimed that he had been given

compassionate leave to await the arrival of the baby, but in fact the leave

had been given for a wedding which never took place, so we later learnt. After

the birth the couple with baby left and were never seen again much to the

dismay of several Tallymen from whom they had made numerous purchases on a

form of hire purchase. The father claimed he never knew where they had gone,

and did not rate the Tallymen’s chances of getting any money back very

highly as the soldier had deserted the Army and left behind large debts.

I should explain that Tallymen sold goods on credit, normally door to door

though some held their goods in small showrooms. They always collected payment

door to door on a weekly basis. We would go down to Horseferry Road near Vauxhall

to one of them and order a new suit, the best ones made to measure at a cost

of about £2.00, and the Tallyman would collect the weekly payments at

our door.

Below us on the first floor lived Mr. Hardiman, a taxi driver. We never saw

his wife as she was suffering from a mental disorder and spent all her life

away. Mr. Hardiman would visit her once a month year after year. He let his

second room to Mr. Flowers, a rather quiet man who left the house very early

in the morning, returning around 7pm. None of us knew what his job was or

where he went. Once home in the evening, he did not leave his room until the

following morning, a small gas ring in his room being sufficient for his needs

of a cup of tea or to warm some food. He lost his job and had to move on.

I saw him walking away, all his possessions in one small case, a very sad

sight for us all. We never saw or heard from him again.

Mum recognised the opportunity to relieve the congestion we

all were experiencing in our two rooms and was able to rent from Mr. Hardiman

the spare room Mr. Flowers vacated. Mr. Hardiman’s rent was the same

as ours, 7/6 pence per week (37p), and he agreed to allow us the use of the

extra room in return for a small sum plus meals on Sundays. We were overjoyed

as up to that time Kitty, Syd and myself slept in folding down chairs in the

kitchen next to the kitchen table and it was very cramped. Before we could

get breakfast the beds were folded up to be chairs. In the summer the heat

was appalling. We were all growing up and getting boisterous. Kitty then was

twelve years old, myself a year younger and Syd was seven. None of us thought

the way we lived in any way odd and just accepted it as the normal way of

life, but we were very confined and there was nowhere to go for a bit of peace.

Mum and Dad slept in the other room on a bed settee. It was always kept tidy

and spotless, and we were careful in there and not at all noisy. We all had

our lunch in their room on Sundays.

Thereafter every Sunday a very good meal was taken down to Mr. Hardiman on

the floor below. After he had finished he always stood at the foot of the

stairs and called up, “Any more potatoes ‘Mrs. H.’”

We never heard him call out “Mrs. Hartland.” It must have been

a very good deal for him as Mum was an excellent cook.

Every morning between 6.30 and 7.00 I would leave home with a carrier bag

and run to the end of Westmoreland Street to join the queue outside the baker's

shop to ask for stale bread. It seemed so normal for we young children from

the whole street to get up as early as a.m. For two or three pence the baker

would fill the whole bag. It never occurred to me until I reached adulthood

that this man in his simple way was helping out all the families the best

way he could by selling bread he had baked the previous day and that from

the amounts sold he must have made extra quantities to cope with the demand.

After a bite of breakfast I was away on the milk round, helping out one of

the deliverers seven days a week for half a crown a week, the equivalent now

of 12p. The milkman was very devious, quite crafty in fact. I clearly remember

starting on a Saturday morning and getting just the half crown paid for the

week. As I had worked two Saturdays, I reminded him and he pretended that

he had forgotten. I got my rightful sum though. He really was tight with his

money and never gave me an extra sixpence at Christmas. If we finished the

round early, he would wait around the corner for a while as he explained he

did not want the boss to know that the round could be completed much sooner.

Our new room was quite good, a bit on the small side but much better than

sleeping in the kitchen upstairs. Syd and I had to share the same bed. Syd,

being the youngest, got shoved up against the wall, this being the worst spot.

He didn’t mind though. Kitty now had the whole of the kitchen to herself,

at least during the night hours. The big snag was when someone caught a severe

cold and had to have space for themselves which involved a lot of upheaval.

The sleeping arrangements continued for several years.

Our front room on the top floor was always known as the “best room”

and, as it was our parents bedroom, we seldom entered it. They slept in a

large bed settee. On the mantelpiece above the fireplace were small ornaments

and around the edge of the shelf was pinned a decorative frieze. In their

room there was also a large wooden trunk holding Dad’s black suit, white

silk scarf and best flat cap.

The suit and shirt were taken out of the trunk on Sundays and

on other special days. After use, they were cleaned and ironed and placed

back inside the trunk along with the long white silk scarf, the cap, layers

of tissue paper and plenty of moth balls. This attire was almost a uniform

for men at that time. However menial a man’s occupation, he would always

be well dressed and clean on Sundays and public holidays.

We had many treats, the best of all was the Duke of Westminster’s party

held once a year in December. Every child in Pimlico was taken by bus to see

a pantomime. As we entered the bus we were given a bag full of goodies, a

cake, some sweets, sandwiches, a little gift and a paper hat. Year after year

we went until we left school. The postmen also gave a party for children at

Christmastime which they saved for throughout the year. In those days postmen

were well dressed in a smart uniform, the hat was almost like a helmet with

a flat top. No one ever saw a postman without a hat on, and his uniform was

kept spotless.

A ten minute walk brought us to the street market on Lupus Street, near Warwick

Way. Several stalls on each side of the road sold all sorts of goods, mainly

vegetables and fruit but sometimes even meat as refrigeration was rare and

the butchers had to sell off any remaining stock. Canned items were on display

and practically auctioned off. All stalls were lit by gas lamps, which made

a hissing sound. It was an exciting place to be. One of my friends from school

was always there helping out his father, who sold only rabbits. These were

hung from a hook complete in their skins and as each was sold, we would watch

him pull the skin off in preparation for cooking. The family name was Davis.

I particularly remember him for being late for school one morning, and as

the teacher demanded to know the reason, he blurted out, “My Dad said

I was not to take any punishment as I was helping him to get the stall ready.”

Mr. Pope, the teacher, said not another word.

The first stall in line was run by an old ginger haired crone. I think she

wore a wig as her hair was always in different positions. She told all the

children that if they came and bought potatoes from her regularly throughout

the year, she would give them a present. I was around six or seven years old

at the time and believed every word she said. Christmas week came and with

some excitement I bought our five pounds of potatoes and asked for my gift.

She chased me away saying, “Clear off you cheeky little urchin.”

A week later she was as nice as pie and tried to entice us with the same promise!

Sunday afternoons a hand bell would ring in the street outside, and we could

hear the muffin man calling out, “Fresh muffins out here!.” A

flat tray would be balanced on top of his head over a clean white cloth. Muffins

cost a penny each and we would toast them in front of our open coal fire using

a long wire toasting fork. During the afternoons we heard the travelling milkman

calling from the open space outside, “Milk a penny a pint.” A

wonderful value, out we would go with jugs and saucepans. Sadly it came to

an end after a few months. He got six months imprisonment for selling watered

down milk.

On Westmoreland Street we seldom saw a car. We played outside most of the

time - scores of us playing marbles, hopscotch, even cricket, in complete

safety. Molestation was unknown, we never even knew the word. When it was

time to go in, a parent would open a window and call out to their child. The

message would be passed along the street until it reached the child concerned.

To a very great extent every family helped each other, particularly when a

new baby was expected. Neighbours took care of each other’s children

whenever they could.

A turning to the right at the far end of Lupus Street led into

Aylesford Street where both my grandmothers lived. No. 30 was the home of

Mum’s mother, a widow who had given birth to nine healthy children,

all living at one time in two rooms on the top of a three story terrace house

in similar style to ours. She was born in Ireland and was named Kate O’Hara.

Like many Irish folks at the time, she moved to England seeking employment.

On arriving in England she met and married a Scotsman named William Percy

Hollidge. Mum was born in 1899 and then followed eight other children, Popsy,

Nellie, Ethel, Lily, the twins Peggy and Emmy, Harry, and the eldest son whose

name I never knew. He died as a result of wounds in the 1914-18 war. Her husband

died soon afterwards.

Gran managed to keep the family going by getting a job as a charlady and office

cleaner at the War Office. This involved an early morning walk from Pimlico

to Whitehall arriving at 6am five days a week, leaving the eldest child to

prepare the younger children and get them to school. This was Mum’s

job and it was not a happy time for her. She was conscious of being poorly

dressed and was very relieved to leave school at the age of fourteen to enter

service. It was quite normal for children to become maids and cleaners for

more affluent families. They got meals and a small attic room, sometimes shared.

Their pay, average £1 per month, was saved for them and given when they

were allowed home on public holidays such as Christmas.

All my aunts and Harry were cheerful despite the cramped rooms. They were

very friendly with the five girls downstairs, whose mother was also a widow

from the war. I being a young boy amongst so many girls got me a lot of attention

from all of them during my visits. There was not much money but a lot of happiness

in that small terrace house. Even Grannie, scrubbing floors to keep her children

fed, I never heard complain.

Kitty, Syd, Ted

FIRST SCHOOL

Just before I was to go to school, an incident occurred which

caused my family some grief at the time. Mum and Dad were both out. Mum was

a cook with Mrs. Levitt’s restaurant over the other side of Ebury Bridge.

I was six years old, Kitty just over a year older, and I was playing with

Ethel Villiers in the backyard of her house next door to ours. Glancing up

to our lids she asked whether I could jump from there into her backyard. I

ran into our house and climbed over the lids wall. I hung by my hands and

looked down. The distance now seemed to be huge. I did not want to let go

and tried to pull myself up but could not. I heard screams from women coming

from Peabody Buildings backing onto our street. My arms weakened and it was

not long before I dropped straight down to the paving stones in the backyard

below. I still remember dragging myself towards the scullery watching my thigh

swelling. I felt no pain at all as I lay there. From upstairs I could hear

Ethel screaming and later learned that she had told Kitty what had happened.

Kitty ran crying to Mum’s workplace over Ebury Bridge. She arrived in

hysterics with tears and smudges covering her face. Later I was told it took

a long time for Kitty to sob out the details.

I awoke in St. George’s Hospital at Hyde Park Corner, my broken right

thigh encased in plaster. The operation was a success and after six weeks

I was discharged and sent for another two weeks’ convalescence somewhere

in Kent. On leaving the doctors advised me that I must not kneel for some

months.

Because of my injury, it was two months before I could attend the class for

six year olds at Warwick Junior School, where boys and girls had separate

classes. We were under the supervision of Ms. Rose. She was a very keen pianist

and tried to imbue in us a feeling for music. At one time she said to the

children in her class that if she had to choose between being blind or deaf

for the remainder of her life, she would choose to be blind. We all thought

it an awful topic to think about.

The Headmaster of the school was named Mr. Ayres, a ginger haired tyrant with

a perpetual scowl on his face. He was so much feared that children hushed

as he walked past them playing. He took every opportunity to cane boys between

the ages of six and ten years, normally three on each hand. His face would

be distorted with anger as he brought the cane down as hard as he could. For

many offences this would be in front of the entire boys school after morning

prayers. I was a regular victim, as was Syd who was caned often for laughing

in class. Teachers would be looking to the floor, no doubt ashamed at the

brutality. But no one protested at the brutal treatment of boys as young as

six. Now I realise they probably wanted to keep their jobs safe.

One event particularly sticks in my mind. After school one Friday evening

three of us, now seven year olds, knocked down some placards outside a newsagents

shop. This was reported to Mr. Ayres, and our names were called out at assembly

on the following Monday morning. I was first to be caned, three on each hand.

I watched his face - livid with anger, hoping the pain would bring tears.

I felt faint and sick, but no tears came. His desk was on a pedestal. I staggered

to this and sat down feeling faint, listening as he beat Fatty Billum and

my other friend getting the same sadistic and brutal punishment. We had no

one to protect us, nor could we protest. Punishments were recorded in a special

book - I often wondered who would want to read it.

Apart from caning, Mr. Ayres also tried to embarrass children

who, due to their parents being quite poor, had to apply for free school meals.

Syd and I were among these at one time. At the end of assembly on Monday each

week Mr. Ayres would dismiss the boys to their classroom with the remark,

“With the exception of those wanting lunch tickets.” Later in

life I came to the conclusion that the man was probably disliked by all he

met, male as well as female, and was probably sexually frustrated, so he vented

his anger with his situation by beating helpless boys who were at his mercy,

probably getting some sexual satisfaction in the act of inflicting pain. Now,

over seventy years later, I can still remember his awful visage.

As Kitty and I did earlier, Syd commenced school at Warwick Junior. After

school was ended for the day Syd and I would walk down Lupus Street to our

home. For some reason we both fainted quite a lot, particularly if we remained

standing. On one occasion Syd fainted outside a shop a short way from school.

He tried to rise up and a man came and pushed me aside, saying that Syd was

having a fit. The man held him down by his shoulders and Syd was struggling

to get up. He was white in the face straining against this man. With all my

strength I managed to push him away. He then disappeared into the shop and

telephoned for an ambulance. It came in quick time and again Syd was carted

off to hospital with me going with him. We never knew the cause of the fainting.

I have often thought of that incident and can still see little Syd ‘s

face as he struggled to get up. Neither Syd nor I ever happened to mention

it over the next 5 years and yet when I brought it up with him just a few

months before he died, I was amazed when he said he indeed remembered it.

I took another part time job at the age of ten with Mr. Short,

a shoemaker. My milk round job was finished by 7. 0 a.m., so during my lunch

break I would run to the shoemaker’s shop from school and collect shoes

needing stitching and take them to a larger shop in Vauxhall Bridge Road,

returning to Mr. Short with those that had been left the previous day. Including

Saturdays, the pay was two shillings and six pence. Mr. Short always added

another two pence for myself knowing that all my pay went to Mum.

Mr. Short had a hard life. He was bent double from being crouched over his

last during the whole of the day. He lived in one basement room with a small

bed, a couple of chairs and not much else. I visited the place a few times

to deliver his shopping and noticed that a knife, fork and spoon were laid

out on a clean white cloth and in the front of the fireplace stood a small

gas ring where he did his cooking.

In the window of his shop were old fashioned shoes and boots left unclaimed

by clients over the years. They were covered in dust but he left them there

as a reminder to the owners to find and collect. No one ever did while I was

there. Some were in the window over twenty years, from the First World War.

After calling at the Labour Exchange to enquire whether any jobs were available,

Dad had started visiting Mr. Short, doing small jobs for him. One Saturday

morning Mr. Short asked Dad, “How can I pay you for the work you have

done for me?” Dad asked for a pair of the unclaimed boots for me. They

were several sizes too large and as I walked to school the next week I thought

to myself at least my feet were dry. This was the reason Dad had chosen them,

but after a two weeks holes appeared in the soles and we had to stuff them

with newspaper.

One day I saw Dad coming through the gate of the school during our lunch break.

It was pouring with rain and my feet were soaking wet when he beckoned me

into an entrance to school hall. Opening a carrier bag, he said, “Put

these on, son.” They were a brand new pair of boots. I was very happy.

Throughout 1934 to 1939 employment soared to four million in England, even

higher in other countries, particularly in the U.S.A. and Germany. The North

of England and Wales suffered badly. On a visit to these areas, the Prince

of Wales (later the Duke of Windsor) expressed his shock at seeing the poverty

and the condition of many of the children obviously suffering from malnutrition.

He said to the newspaper reporters and the civic members of the local councils,

“Something must be done.” On his return it is recorded that he

visited Garrards, the Crown jewellers, and purchased an emerald and diamond

necklace costing £30,000 for Mrs. Simpson, and nothing was ever ‘done’.

As we now know, the Duke of Windsor visited Germany with Mrs. Simpson prior

to the outbreak of war and met all the leaders of the Nazi party, shaking

hands with them. He was then sent to a very safe abode by being made the Governor

of Bahamas on the outbreak of the Second World War. There he lived a life

of luxury while millions were slaughtered. He should have done better. A weak

man with very little compassion for any other person.